Typically, in a strategy game, in addition to the triangle mesh that we use to draw the terrain, there is an underlying logical representation, usually dividing the terrain into rectangular or hexagonal tiles. This grid is generally what is used to order units around, construct buildings, select targets and so forth. To do all this, we need to be able to select locations on the terrain using the mouse, so we will need to implement terrain/mouse-ray picking for our terrain, similar to what we have done previously, with model triangle picking.

We cannot simply use the same techniques that we used earlier for our terrain, however. For one, in our previous example, we were using a brute-force linear searching technique to find the picked triangle out of all the triangles in the mesh. That worked in that case, however, the mesh that we were trying to pick only contained 1850 triangles. I have been using a terrain in these examples that, when fully tessellated, is 2049x2049 vertices, which means that our terrain consists of more than 8 million triangles. It’s pretty unlikely that we could manage to use the same brute-force technique with that many triangles, so we need to use some kind of space partitioning data structure to reduce the portion of the terrain that we need to consider for intersection.

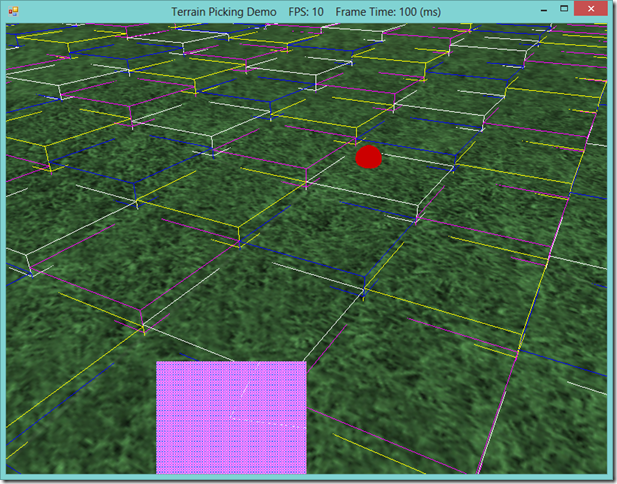

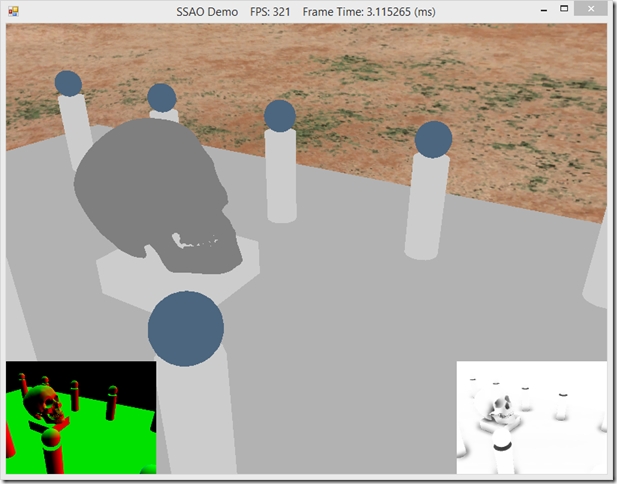

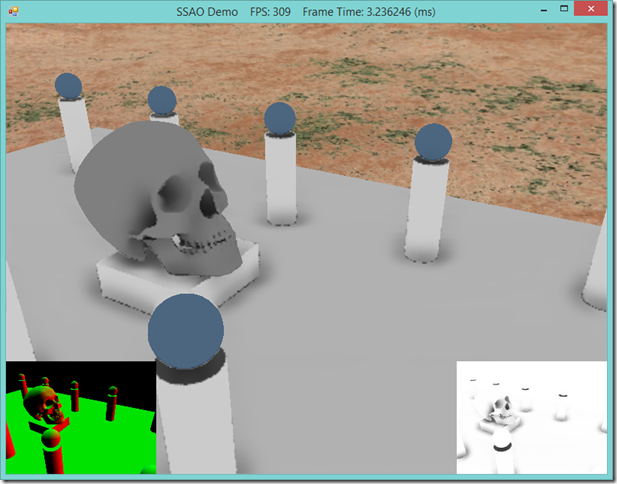

Additionally, we cannot really perform a per-triangle intersection test in any case, since our terrain uses a dynamic LOD system. The triangles of the terrain mesh are only generated on the GPU, in the hull shader, so we don’t have access to the terrain mesh triangles on the CPU, where we will be doing our picking. Because of these two constraints, I have decide on using a quadtree of axis-aligned bounding boxes to implement picking on the terrain. Using a quad tree speeds up our intersection testing considerably, since most of the time we will be able to exclude three-fourths of our terrain from further consideration at each level of the tree. This also maps quite nicely to the concept of a grid layout for representing our terrain, and allows us to select individual terrain tiles fairly efficiently, since the bounding boxes at the terminal leaves of the tree will thus encompass a single logical terrain tile. In the screenshot below, you can see how this works; the boxes drawn in color over the terrain are at double the size of the logical terrain tiles, since I ran out of video memory drawing the terminal bounding boxes, but you can see that the red ball is located on the upper-quadrant of the white bounding box containing it.